Meeting the Blues at the Crossroads: My Lifelong Love for Son House

Somewhere in the middle of a scratchy old record, I met a voice that felt like it came from the earth itself—raw, ragged, full of thunder and sorrow. That voice belonged to Son House. And nothing in my musical life has ever been the same since.

I didn’t find Son House through radio or recommendation. I found him digging through an old blues compilation in the corner of a record shop—the kind of place where the lights are dim and the dust carries stories. I picked up Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions because I’d heard the name before in reverent tones. I didn’t know I was about to get hit in the chest by something realer than anything I’d ever heard.

The First Note That Broke Me

When I dropped the needle on “Death Letter,” my knees damn near gave out.

That slide guitar—gritty, wild, unpredictable—sounded like it had been dragged across broken glass and soaked in Mississippi mud. And then his voice. Oh man, that voice. It didn’t sing so much as testify. It shouted from the edge of a life full of pain, regret, God, and redemption. It was a sermon. It was a confession. It was the blues in its purest, most human form.

That one song told me more about life, loss, and spiritual survival than years of school or sermons ever could.

A Preacher, A Drifter, A Survivor

Son House wasn’t just a musician—he was a preacher who couldn’t shake the devil’s music. That contradiction fueled everything he did. Born Eddie James House Jr. in 1902 in Mississippi, he started as a Baptist minister. But the pull of the blues—those steel strings and that slide—was too strong to resist.

And that tension never left him. You can hear it in every track. Songs like “Preachin’ Blues” and “John the Revelator” aren’t just about religion or music—they’re about wrestling with the soul. The man didn’t play for your ears—he played for your truth.

He recorded a few sides for Paramount in the 1930s, then disappeared—like so many Delta musicians of that era. And that might’ve been the end of the story if not for one of the greatest rediscoveries in music history.

The 1960s: Son Rises Again

When the blues revival hit in the ’60s, Son House was dragged back into the spotlight—literally. Alan Wilson (who would go on to form Canned Heat), along with a few blues historians, tracked him down in Rochester, New York, in 1964. The man hadn’t played in years. They put a guitar back in his hands—and the fire came roaring back.

His 1965 Columbia sessions are the stuff of legend. To me, that’s where the real Son House lives. Older, slower, but deeper. When he sings “Grinnin’ in Your Face,” it’s just his voice and his hands. No guitar. No backup. Just him, clapping and warning us: “Don’t you mind people grinnin’ in your face.” If there’s a more direct line from artist to listener, I haven’t heard it.

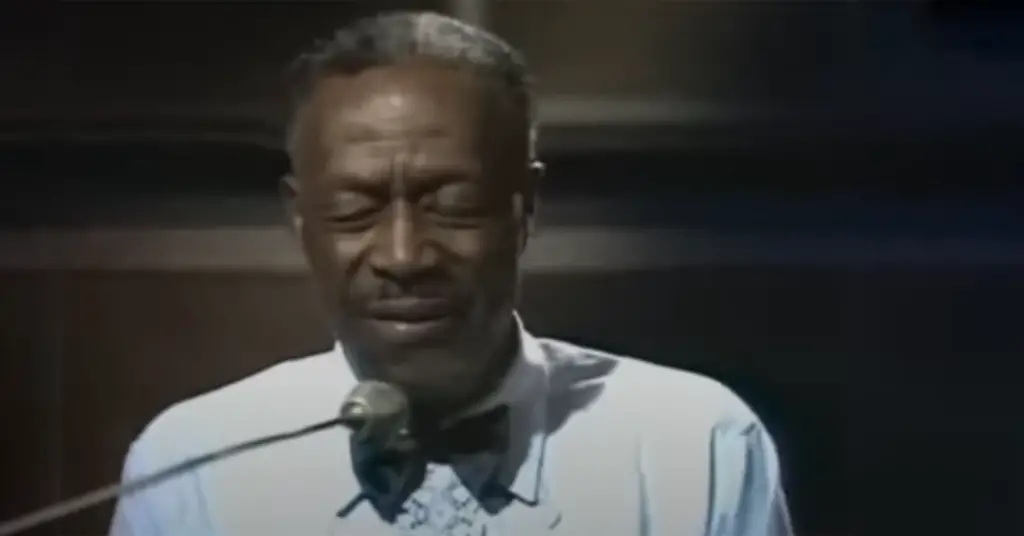

Seeing Him in Old Footage

I never saw Son House live—he passed in 1988, and I came to him too late. But I’ve watched every grainy clip I could find. In those black-and-white frames, you see something sacred. His eyes close. His body shakes. His slide hand moves like he’s possessed. It’s not performance. It’s release. Like he’s purging demons in real time.

Even when he could barely play due to age or arthritis, his presence filled the room. The guitar might stutter, but the truth never did.

Why He Still Matters

In a world of overproduction and overthinking, Son House is a thunderclap of authenticity. No polish. No perfection. Just the raw sound of a man searching for God and wrestling with the world through a beat-up steel guitar.

He taught me that music doesn’t need to be pretty. It needs to be honest. That the crack in the voice is where the feeling lives. And that sometimes, the heaviest sound comes from a single voice and six strings.

For the New Listener

Start with Death Letter. You have to. Then go straight to John the Revelator and Preachin’ Blues. After that, dive into the 1965 Columbia recordings—every track a masterclass in grit and gospel. If you want to go deeper, find those early 1930s Paramount sides—low fidelity, but higher truth.

If you’re really serious, hunt down some video footage on YouTube or in old documentaries like The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins. Seeing Son House in motion changes everything.

Son House didn’t just sing the blues. He became the blues. And once you’ve heard that sound, you carry it with you. Like a scar. Like a gift. Like a reminder that even in sorrow, there’s something sacred worth shouting about.

Thank You

We appreciate your time and dedication to reading our article. For more of the finest blues guitar music, make sure to follow our Facebook page, “I Love Blues Guitar”. We share exceptional selections every day. Thank you once again for your continued support and readership.

Facebook Comments